Agent of change: Alumnus is a nationally renowned attorney hailed a "legend” and “legal titan"

Elliott Hall has earned a slew of awards and honors in the course of his career, including the President's Award from the National Bar Association. A 1965 alumnus of Wayne State University Law School, Hall was the first African American to serve as corporate counsel for the city of Detroit, and the first African American to serve as a vice president for Ford Motor Co.

But, in a way, his celebrated career got its start when Hall was a paperboy for the Detroit News in the 1950s and still a student at Chadsey High School.

"I was an exceptional paperboy," Hall said. “I went out and got new customers. When I was 16, they made me a station captain in charge of about 10 boys. When I became a station captain, I was interested in working for the Detroit News when I got out of high school. They promised me a job as a jumper on the truck. The jumper would throw the papers into the newsstand. Then I could move up to truck driver.

"But one month before my graduation, the manager told me they weren't hiring colored people. I was driven to tears. I had been promised the job for two years."

The injustice became a "pivotal moment" in his life.

Trailblazer

Hall wasn't much of scholar in high school, but he decided then and there to go to college and then to law school. He thought that as an attorney, he could make a difference, be "an agent of change" and improve the lives of African Americans.

"I had no idea where this law degree would take me," he said. “I just thought I had to contribute to the community in some way. At the time I graduated, I knew every black lawyer in the state of Michigan. There weren't that many."

He worked for a few years in the insurance department at Chrysler, and in 1967, began practicing law with S. Allen Early.

"He was a brilliant trial lawyer, a former Wayne County assistant prosecutor," Hall said. "I picked up a lot of my technique from him. I moved around quite a bit when I started practicing."

Hall also worked with the late Ernest Goodman, a 1928 graduate of Wayne Law (then Wayne State College), a preeminent civil rights lawyer and another mentor for Hall. He joined Goodman Crockett Eden and Robb, the nation’s first integrated law firm.

"In 1967, the Detroit riots occurred, and lasted for an entire week," Hall said. "As a young criminal lawyer at that time, I was very busy that week."

The city imposed a curfew, and thousands of people were arrested for violating it – so many that there was no place to put them.

"Some were held in the bathhouse on Belle Isle, some were held on buses," Hall said. "The courthouse was open 24/7."

Eventually, the lawyers got almost all the curfew violation cases dismissed.

Hall left the Goodman firm, and started a practice with fellow Wayne Law graduate Samuel Gardner, who went on later to be the chief judge of Detroit Recorders Court. Next, Hall and some friends formed the law firm of Hall Stone Allen and Archer.

"That's when I started doing work for the Black Panther Party," Hall said. "They tried to sell self-published newspapers in downtown Detroit, and many times they were arrested for that. I felt that was not appropriate."

In 1970, after an altercation between police officers and some Panthers trying to sell their papers, police were called to a house in west Detroit where many Panther members were living. When a responding officer got out of his car, he was shot dead from a window in the house. A standoff ensued.

"I was called to the house to see if I could engage in a peaceful surrender of them," Hall said. “We were able to bring 12 or 13 of them out. Three others decided they wanted to shoot it out. Officers lobbed tear gas. They were all charged with murder. Ernest Goodman became lead lawyer (in the Panthers' defense) and I was the second lawyer. We went to trial and it was a very interesting case. The only three Panthers convicted were the three that stayed in the house. All the others were acquitted and set free.

"These were not typical criminals. They were social activists who wanted change, and fair treatment for all citizens."

In 1974, shortly after taking office, new Detroit Mayor Coleman Young tapped Hall, who at the time was president of the prestigious Detroit branch of the NAACP, to serve as corporate counsel for the city. Hall was now in charge of 40 other lawyers, and considers that posting as "the first major break" in his career. In that role, and after he left a year later to practice privately again, Hall was able to play a major role in the integration of the city's Police and Fire Departments.

In 1983, he was appointed by Wayne County Prosecutor John O'Hare as chief assistant prosecutor. Hall was the first African American to hold the post.

"He put me in charge of the criminal division in what was known as Recorders Court," Hall said. “It was mainly an administrator's job. We had 90 assistant prosecutors to cover the myriad of crimes that took place in the city. But instead of being a complete administrator, I did try some high-profile cases. I wanted to keep my skills as a trial lawyer.”

In 1985, he joined Dykema Gossett Spencer Goodnow and Trigg and became the firm's first male African American partner. At Dykema, he worked on and won a case that involved Ford Motor Co., and impressed the car company's leadership.

Next steps

In June 1987, Ford executives recruited Hall to serve as their vice president of governmental affairs, making him the huge car company's first African American vice president. When Hall got the phone call confirming the job, he immediately thought of his father, who had worked in the Ford Rouge plant foundry – "that dirty, grimy furnace room" – for nearly 40 years.

Said Hall: "I got up from my desk at Dykema, went to the parking garage, got in my car and drove to the cemetery where my father was buried. I told him about the job. I talked to him as if he was alive. I had to extend my gratitude to him for many things, for being a family man, for keeping the family together."

Hall moved his family to Washington, D.C.

"That was a major stage of my life," he said. "It took me out of a pure legal career into a lobbyist career. I got a lot of prestige and lot of attention."

In Washington, Hall continued the extensive community work he had begun in Detroit, serving on the boards of the National Symphony Orchestra, the Washington Performing Arts Society, Georgetown University, the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation and in many other ways. In Detroit, he had served as president of the Detroit Bar Association and the Wolverine Bar Association, as chairman of the board of the Family Service of Detroit and Wayne County, as a board member for the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and as a trustee for the Community Foundation of Southeast Michigan, to name just a few of his volunteer services.

In 1998, he became Ford's first African American vice president of dealer development.

Hall retired from Ford in 2002, and rejoined Dykema as a senior partner.

Today, the 81-year-old former paperboy who was denied a job because of his race looks back on his legendary legal career with pride and pleasure.

"I have never regretted the day I walked into the law school at Wayne State University," Hall said.

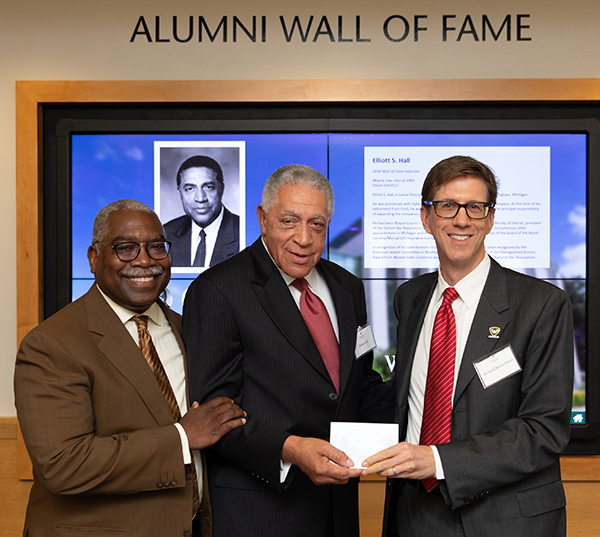

In 2018, he was named to Wayne Law's Alumni Wall of Fame.

Six questions with Elliott Hall

Q: Why did you choose to study law?

A: When I started law school in 1961, there was still rampant discrimination throughout the country. I knew that by pursuing lawsuits, change could happen and would improve the lives of African Americans. The Civil Rights Act passed in 1964, and the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965, but just the passage of those acts did not overnight create great advantages for African Americans. It's a constant battle to maintain a level of being aware and addressing problems. It's still a struggle.

We are absolutely going down the wrong track now. We are probably the most diverse country on this earth. Diversity is a part of the United States, and we have a president who has decided he wants to divide the county. It is absolutely intolerable. I hope we can return to conduct that is required by pure Christian values. It is up to lawyers, I think, to sort of guide the way.

Q: You have been noted often for your integrity. How do you convince law students and beginning lawyers how much integrity matters in the practice of law?

A: Our system cannot operate without a series of laws and rules of conduct. As a lawyer, you become one of the architects of that system. You are required to maintain the laws that established the system, and sometimes to improve them. You cannot do that if you're dishonest. The practice of law is a very honorable profession.

Q: You've been honored many times. Is there any one honor or award that stands out to you?

A: In 1985, Wayne State University Law School honored me with its Distinguished Alumni Award. I'll never forget it. I have the plaque framed. At the time, I was chief assistant prosecutor for Wayne County.

Q: Who are some of your role models and why?

A: My grandfather, Frederick Douglass Burton, was an inspiration early on. I had some local ones: (U.S. Circuit Judges) Wade McCree and Damon J. Keith – these were major forces. And my parents: My mother and dad ran a strong, righteous household. I never entered my house from school or whatever I was doing that my mother was not there. I appreciated her strong presence and advice. My older sisters and brothers (Hall is the second youngest of eight children, one of whom, an older brother, died before he was born) were also very supportive.

I was the only member of my family who got a four-year degree, and when I was going to college, if I needed a car or some extra dollars, my older brothers and sisters were always there to help me. My family was extremely proud of me.

And while I am proud of my professional achievements, my wife and children are a source of much pride. I have a son and two daughters. My son Fred operates a growing security business in Detroit. My older daughter Lannis is a medical doctor in St. Louis and the younger daughter Tiffany is an attorney in New York City.

Q: What do you do in your spare time?

A: I still play golf a little, but my hobby is classical music. I tried to play drums in grade school, but I was not very good. My sister, Anelda Hall McKenzie, was a great pianist and organist. My brother, Seabron Hall, was chief violinist in his high school orchestra. We had music in the house all the time. I didn't play, but I ended up collecting CDs of classical music. I have hundreds and hundreds. I also do a lot of reading. When I was a Ford lobbyist in Washington, I had to read newspapers every day: The Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and, of course, The New York Times. That's a habit I still have today.

Q: Please describe yourself as a 12-year-old growing up in Detroit.

A: At 12, I had started my first job in a fish market. I was raised in a house where I had three brothers and two sisters who were older than I was. I always saw them going to school and work, so that was my mission then. I wanted to own a house and have a family.

Assets

- Elliott Hall speaks with Dean Richard A. Bierschbach during a Dean's Speaker Series event (jpg)

- Elliott Hall stands at the podium during a Dean's Speaker Series event (jpg)

- From left, Judge Edward Ewell Jr., Elliott Hall and Dean Richard A. Bierschbach together at the Wayne Law Alumni Wall of Fame induction ceremony in 2018. (jpg)